Maidan: "Dictatorial Laws" of January 16th

A crucial development in the course of the Euromaidan, which made it clear to the protesters that there was no way back, these events seem more relevant than ever

On 21st of November 2013, Yanukovych broke one of his main election promises (allegedly, after a meeting with Putin where he was both intimidated and bribed).

As President Yanukovych was speaking in Vienna, saying that “Ukraine is and will be on the path of Eurointegration,” his loyalist Prime Minister, the corrupt and hilariously pro-Russian Mykola Azarov, issued a directive to the government to “halt the preparations for a signature of the association agreement” with the EU and its member countries. Instead, the directive ordered to begin dialogue on closer economic ties with Moscow while relegating Eurointegration efforts to a potential three-sided dialogue between EU, Ukraine, and Russia.

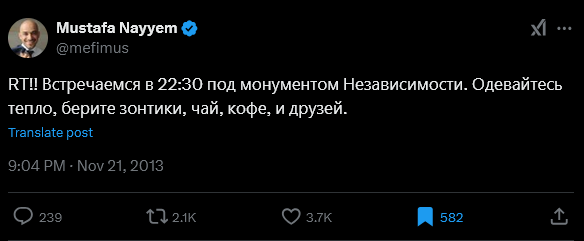

The reaction among Ukrainians was a mix of shock and fury. Some who saw the Yanukovych government for what it was were not surprised, but prepared. Activist Mustafa Nayeem posted a soon to become legendary call to action on his social media that would be the first push of the Revolution of Dignity:

“Retweet! Let’s meet near the Independence Monument at 22:30. Bring warm clothes, umbrellas, tea, coffee, and friends.”

The following days saw mass actions and marches, primarily by the student and activist demographics, as well as an increasing presence of special police units in Kyiv.

On the 30th of November, a regiment of the “Berkut” Special Purpose Unit kitted out with riot police gear attacked the protesters, eventually surrounding them in the center of the plaza around the Independence Monument itself. There they were beaten relentlessly by the police, with dozens of arrests and 74 protesters injured by morning. This attack was televised on most Ukrainian news channels in all its brutality, shocking the entire nation. Yanukovych succeeded in clearing the Maidan from protesters, but not for long. In Ukraine, this event is considered the end of the “Euromaidan” and the start of the Revolution.

On the 1st of December, protesters returned - now not in thousands, but hundreds of thousands (some estimates put the number at one million people). So did “Berkut” and other riot police units, clashing with the protestors near the Presidential Administration building in the evening, injuring 112 activists and 45 journalists. However, the main group of protestors on the Independence Square remained in place, setting up camp. As the journalist Yurii Butusov put it:

The “Berkut’s” attack divided everyone into two camps - those who demanded justice and prosecution of the policemen, and those who were ready to justify any crime committed by this government.

On that day, it became clear that our society had plenty of those who were ready to fight, who had nothing to lose. […] Ukraine shook off it’s government that dared to infringe on the freedom and rights of its people, that attacked those who decided to fight for the European choice.

The rest of December saw increasing organization among the protestors, as well as a slowly boiling escalation in clashes with the police. Barricades were erected on the streets leading up to the Square. A large stage was built, where various opposition politicians - Oleksandr Turchynov, Petro Poroshenko, Vitalii Klichko and many others - would attempt to steer the popular protest to their favor. A grassroots self-defence militia (armed with captured riot shields, bats, sticks, pepper spray, and in large clashes Molotov cocktails) emerged, eventually becoming organized into some three dozen “Sotnias” (hundreds) governed by protestor councils and the “Maidan commandant" Andrii Parubii. On the 11th, 5000 riot policemen faced off with 12,000 “Sotniks” in a largest assault on the Maidan so far, failing to achieve a significant result.

As the police was repeatedly unsuccessful in its attempts to disperse the different crowds of protestors branching out of the Maidan, the atmosphere on the Maidan remained jovial. Protestors were convinced and determined, while the political figures grew bolder in their declarations.

In response, the government increased its use of hired thugs to attack and intimidate the Maidan’s real workhorses - leading activists and journalists. A prominent anti-government journalist Tetiana Chornovyl was attacked by such thugs on the 25th and severely beaten up, turning her into another martyr figure and further enraging the protestors.

By the new year, the revolutionaries in the center of Kyiv and many other major cities were only becoming more numerous, organized, and entrenched. The Yanukovych government finally understood just what sort of danger it was facing, and began to act accordingly.

Party of Regions members Volodymyr Oliinyk and Vadim Kolisnychenko introduced a package of 11 laws and a directive. The laws were all introducing new punishments for new absurd violations: driving in a column of over 4 vehicles was punishable by confiscating the car and the driving license for two years; writing and publishing as an “unlicensed” outlet was punishable by confiscation of equipment and a large fine; setting up a tent or any other sort of structure without approval by the police was punishable by 15 days in jail, while participating in a protest wearing a helmet or a camo coat was punishable by 10.

If those seem silly and small, the spreading of “extremist materials” was punishable by 3 years in prison, while participation in “mass unrest” was punishable by up to 15 years; the “gathering of information” about a judge or a policeman was punishable by 3 years, while “threatening” a policeman was punishable by 7; the government received a right to issue a partial or complete shutdown of internet; an MP could be issued a warrant and arrested right at a parliamentary assembly; financing of an NGO would require a government permit, and violators of these laws could be sentenced in absentia while police officers charged with excess violence towards protestors were pardoned.

On January 16th, these laws were “approved” in an equally absurd fashion. Vice Speaker Ihor Kalietnik introduced the package to a vote. After the amendment to the criminal code to allow sentencing in absentia lacked enough votes, Kalietnik approved… a vote by hand. Just seconds later, Oliinyk declared that 235 voted “yes.” He would later admit that he didn’t even bother to count - 235 was just the number of Party of Regions and Communist Party MPs present.

The laws were immediately condemned by the US, the EU, dozens of NGOs and the entirety of Ukrainian civil society. But the intent behind them was not intimidation, as it expectedly only fanned the flames of popular fury. The Yanukovych regime did not expect to scare a million determined revolutionaries back into homes. The real purpose of these laws was to set the ground for an unprecedented political persecution once the revolutionaries were defeated by force. Within a matter of days, the Ministry of Interior will launch it’s hardest attempt to break through the barricades to date, and inflict the first fatalities on the protestors. But that is a different story for a different article.

The way the Yanukovych regime decided to solve the crisis as well as the rest of the events of mid-January, the middle point of the Revolution, made it an all-or-nothing game for both the regime and the revolutionaries. Despite continuous efforts by the EU and others to foster a negotiated solution between the opposition and the regime, the real force behind the Maidan - the journalists and activists, the various councils, the volunteers cooking hot soup and tea, the musicians, the army veterans and IT workers, the football ultras and anarchist groups, and everyone else on the barricades and behind them - understood clearly that there could be no stepping back now.

But it’s impossible to not see similarities in the playbook that the Yanukovych government tried to implement, and the laws that were eventually successfully implemented in Russia, in Belarus where the government succeeded in crushing the 2020 revolution, now in Georgia where the initially strong protests with strong political backing seem to be on their last legs. Discussions about similar laws are taking place across much of Europe as well, recently rejected in a vote in Bulgaria, and can only be expected to become more mainstream. But worst of all, implementation of similar laws seems to me to be inevitable in Trump’s second term.

I can not preach lessons, as I had never participated in events such as this. But a revolution lives as long as does the determination of not just the radicals, but the general populace. Even if a good half of the country supports the government crackdown, all that the other side has to do is not fall prey to intimidation and fatigue. A protest’s worst enemy is time.

Thank you for reading! This is the first piece on the Maidan on Casus Belli, but far from the last. I will write more to help people understand the context and the real story of the Revolution of Dignity within the coming weeks, with (maybe) a long-form overview of the whole story to be posted on the Revolution’s 11th anniversary. If you wish to support my efforts, please consider donating at my Buy Me a Coffee as I currently have issues preventing me from receiving subscription payments from here.

Eternal glory to the defenders of Ukraine.